The University of Paris 8, wrote one philosopher, was a “banlieue university” (Brossat 2003). The banlieue university, in such a context, is a paradoxical social form, a dominated branch of a dominant institution, a marginalized site in a major city. Banlieue universities often displayed a love-hate relationship to the banlieue: they embraced and rejected their own surroundings.[13] On one hand, Paris 8 had began to take on the banlieue’s social and aesthetic characteristics, and it integrated with it socially, drawing from the banlieue both its students and its workforce. (The Paris region is quite large, and only one in four students actually lived in the stigmatized “Department 93,” which encompassed Saint-Denis and its immediate surroundings).[14] Yet Paris 8 also resisted the banlieue in institutional terms, seeking to remain a space apart, a guarded space, a securitized space. The first time I ever visited the campus, I was struck by two things: the omnipresent graffiti, and the equal and opposite proliferation of walls, bars and surveillance systems. I would read this graffiti as the becoming-banlieue of the campus, and the security apparatus as the effort to keep the banlieue at bay.

The very notion of a banlieue, it must be said, has become integral to French processes of violent racialization.[15] The operative regime of racial recognition in France is enforced by the state apparatus and its categories of official visibility. The French Republic is officially “color-blind,” so ethnoracial statistics are not collected by state agencies (Simon 2008). This statistical blindness does nothing to prevent institutional or ideological racism among the population, nor to prevent the French police from practicing racialized street harassment (Silverstein 2004). In public discourse, meanwhile, a series of proxy categories became stand-ins for racial markedness: whether one is an “immigrant”; if so, of African or Arab “origins”; whether one is a Muslim; whether one lives in the “banlieue”; if so, the “scary” part of the banlieue; whether one lives in public housing (cités HLM)…

All of these are so many bad metonyms for a system of entrenched racial recognition that singles out Black and Brown people for labor exploitation and structural violence. Dominant French ideological systems work to reproduce an internally demonized Other, albeit strictly on condition of plausible deniability.[16] Inadmissible racial prejudice and anxiety was made respectable by projecting it onto a fear of the banlieue, which thus became a national object of racial misrecognition. What then is a banlieue? Like its closest English-language analogue ghetto, the banlieue designates a space of urban poverty that has acquired a massive symbolic force, above all in dominant white culture. In France, the urban centers have often been preserved as bourgeois enclaves, while spaces of social exclusion are pushed physically to the urban margins (Wacquant 2008). The term is literally translated as suburbs, and there are plenty of affluent white banlieue cities, but given the term’s pejorative assocations, I have often wanted to translate it as outskirts. In dominant French culture, the banlieue can readily come to signify abjection, desolation, violence, poverty, marginality, religious alterity (Islam), national alterity (foreigners, immigrants), racial alterity (Blackness, Arabness), criminality, terrorism, danger and death. This structure of violence was perfectly apparent to banlieue inhabitants. “France has become a nightmare, Islamophobia and racism are always surging up,” declared Adel Benna in 2015, ten years after the death of his brother in Clichy-sous-Bois.[17] The police who had chased his brother were acquitted of all crimes. He left the country permanently.

This, then, was the banlieue: the symbolic opposite of the bourgeois centers of cities such as Paris. While the public university in France was historically a bourgeois institution, its social location has been downgraded as it was increasingly opened to the masses since the Second World War.[18] Whence the ambiguity of the University of Paris 8, a banlieue university full of subaltern graffiti and patrolled by security guards. Via the security apparatus, the banlieue was collectively constituted as the outside of the Paris 8 campus, and not as a zone continuous with university space. Whether the banlieue was coming “in” or being kept “out,” it was made to signify a beyond. This was of course not without ambiguity, nor was it solely the doing of the campus community. In 1980, in an apparent effort to undermine the success of a leftist university, the French state apparatus had relocated the university from the Bois de Vincennes to a new site in Saint-Denis — a site that was intentionally tiny, cloistered, and inaccessible.[19] The Communist-run government of Saint-Denis was hostile to the campus leftists, and the university initially refused to engage with its new neighborhood (Berger, Courtois and Perrigault 2015:123–132). Gradually the municipal government had become friendlier towards the campus, and efforts at community engagement became more numerous. But along the way, the campus community had come to accept a categorical division between inside and outside, and it worked to police this division.[20]

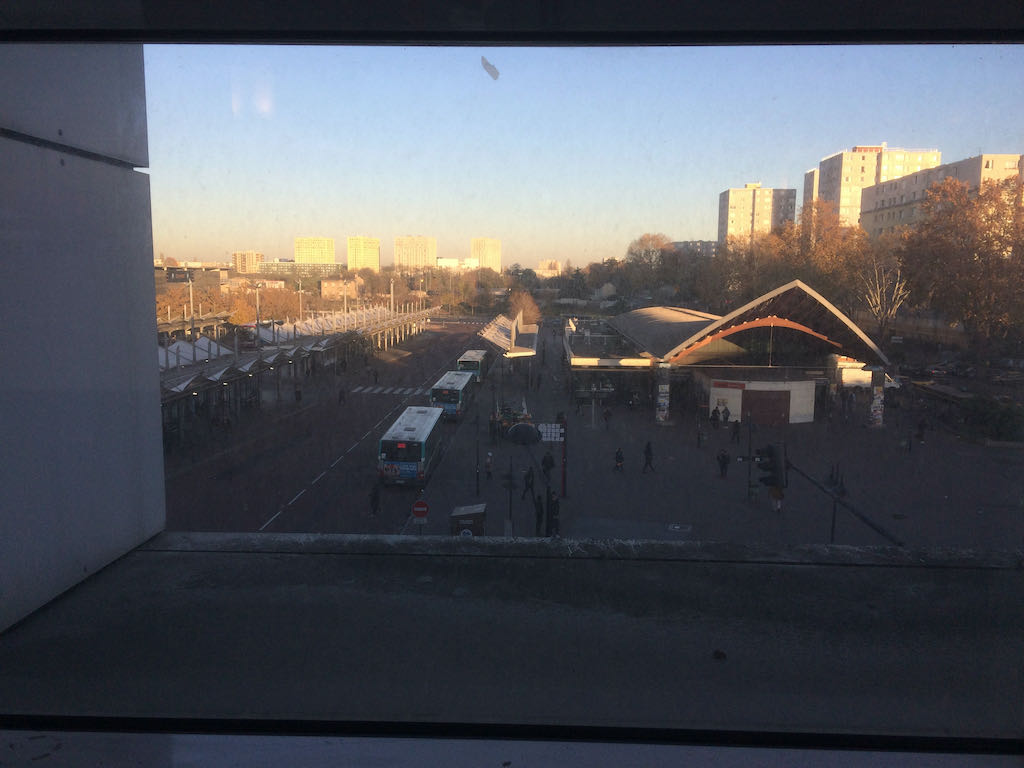

The urban geography of the campus reinforced this divide, since the campus was surrounded not just by walls and guards, but also by a somewhat unfriendly urban infrastructure. To the east of the university was a stretch of empty lots; to the west, a long, empty sidewalk led away under a highway bridge. A few modest restaurants sat across the street, but there was no real business district. Since a majority of the university community lived outside Saint-Denis, most campus visitors remained disconnected from the neighborhood. It was common to come and go by bus or metro, never setting foot past the plaza at the campus entrance.[21]

Broadly speaking, it seems to me that a banlieue university such as Paris 8 served three major functions in its urban economy. It was a site of social reproduction, in its role as an educational institution that tended to filter racialized, working-class subjects into “pragmatic” tracks, while offering artistic and academic tracks more readily to elite subjects. It was a site of racially divided and gendered labor, in its role as a major local employer. And it was a site of ideological production, in its role as a producer of social and academic knowledge, historical consciousness and ideological anxiety. The racialized spaces of the Paris 8 campus cut across all three of these functions.

As I suggested above, the spaces of the campus came to dramatize the two opposed processes of becoming-banlieue and securitization-against-the-banlieue. We will see later how at Paris 8, subaltern labor came into conflict with subaltern dwelling, as one set of working-class subjects confronted another (Chapter 4). Meanwhile, the halls of the campus gave a more frictionless passage to the site’s more privileged actors: the largely white and French professoriate, and the more ambiguously placed population of postcolonial intellectuals. All this puts a further question on our critical agenda. What kind of utopia can emerge from racialized spaces?

In sum, then, the analytical questions that concern us are: What are the material preconditions of a utopia? What kinds of ambivalence organize our possible relationships to liberation? What kind of utopia can be a vehicle for left patriarchy and racialized work? What kind of life is possible in a banlieue university? And more existentially: What if anything can we learn from this case?

-

While elsewhere in the book I work primarily with a more affective sense of ambivalence, here I have in mind a more structural or institutional form of ambivalence, in the sense that institutions can collectively manifest contradictory relationships towards particular subjects, objects or spaces. ↩

-

Méhat and Soulié (2011:16n31) cite data from the Observatoire de la Vie Etudiante, which indicated that in 2010, 24.1% of students lived in Department 93 (Seine-Saint-Denis). ↩

-

I must say that it remains fraught to write about race in France. Achille Mbembe has argued that France is distinguished mainly by its national will to ignorance about its own racial projects (2017:62–77). One common French argument runs that, since race is not a scientifically valid category, it does not exist. Perhaps racism exists, some would concede, but not race. As scholars like Etienne Balibar have pointed out, the “theory” beneath racialization has shifted over time. Today in France, ”race“ has largely deprived of its former ideological grounding in racial science, and Balibar correctly notes that “the idea of ‘race’ is getting recomposed, for instance by becoming invisible” (2013). But I do not find it helpful to borrow his expression “racism without races,” since it makes it harder to make sense of the fact that French subjects constantly recognize and get recognized in racial terms, and one has to make sense of racial location and racial structure, not just racial prejudice and racial violence, to understand the continuing racialization of France. The problem is that racism, whether construed as a prejudice, a practice (e.g. pervasive police harassment) or structural violence (poverty), obviously presupposes some underlying racial logic of identity and classification. Such logics clearly do not need to be “grounded in science” to exist; they need only be embedded in institutions and collective dispositions. ↩

-

This system has responded to genuine shifts in political priorities; as Emile Chabal points out, the 1980s Socialist government was more open to a multicultural “right to difference,” while subsequent “neo-Republicans” prioritized integration into putatively secular French society (2014:238). ↩

-

“Émeutes de 2005 : ”La France est devenue un cauchemar“, estime le frère de Zyed,” RTL, October 10, 2015, https://www.rtl.fr/actu/debats-societe/emeutes-de-2005-la-france-est-devenue-un-cauchemar-estime-le-frere-de-zyed-7780252973. ↩

-

Historically, the university has been an institution of power and elite privilege, and before the post–60s bourgeois flight away from the French public universities (Bourdieu 1996), the university fit solidly into this dominant pole of French public culture. Yet already by 1968, as the universities were “massified,” elite reproduction felt threatened. “We are no longer assured of our future role as exploiters,” said some of the student protesters (Feenberg and Freedman 2001:82). In subsequent decades, the public university was progressively declassed in French public culture, portrayed as an institution of last resort for those with means (Beaud et al. 2010). Sociologically speaking, though, the university remained an institution of class stratification (Bodin and Orange 2013), and even if academic work itself was full of precarity (Rose 2016a), the French public university remained a space apart, energized by its own dominance hierarchy. ↩

-

There was no metro station at Paris 8 in its first years in Saint-Denis; one had to take the metro to downtown Saint-Denis and then continue by bus. ↩

-

For instance, it was only in February 2008 that the university formed an explicit partnership with the regional government of Seine-Saint-Denis to advance their common interests. See the “Charte de partenariat” (Département de la Seine-Saint-Denis, Université Paris 8 Vincennes–Saint-Denis), 19 Février 2008, https://www.univ-paris8.fr/IMG/pdf_Charte_Paris_8_CG93.pdf (accessed 8 December 2018). ↩

-

I only began to understood the banlieue when I stopped taking the metro to campus. To save money, I began to bike to Saint-Denis from my apartment in northern Paris. The more time I spent on the tangled streets leading to Saint-Denis, the less I was ever able to see anything like a stark divide between one space and another. Instead, I came to see the very notion of a banlieue as a cultural category that fundamentally works to mystify racial capitalism in France. To speak of a banlieue does not help us comprehend the web of infrastructure, social barriers and flows that comprises the regional economy of Paris. The very notion of the banlieue too readily cuts up this interconnected socioeconomic world, dividing it into marked and unmarked spaces, into centers and peripheries. In a postcolonial society, one cannot comfortably presume a distinction between centers and peripheries. ↩