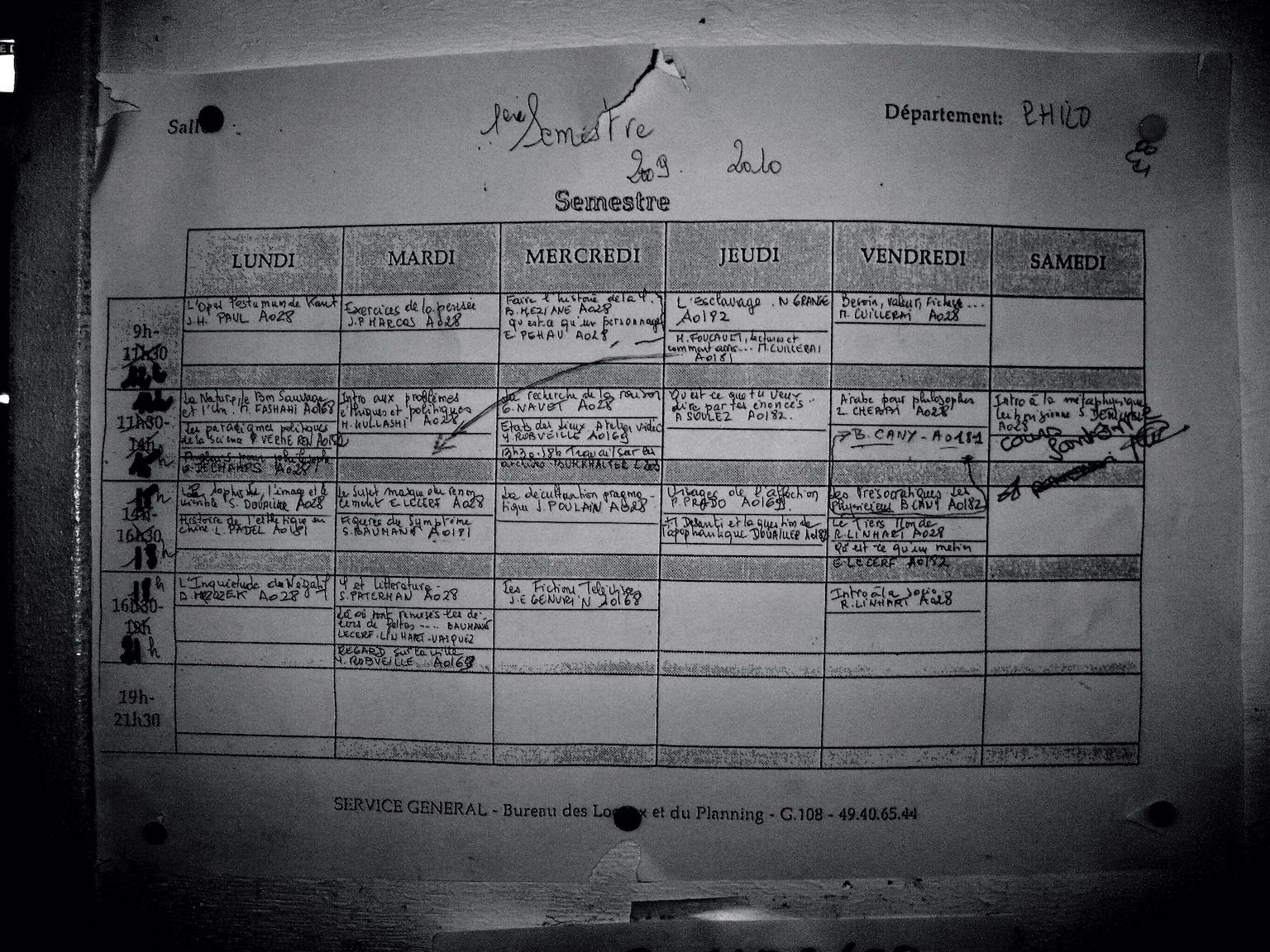

I arrived one day at the department office one day in March 2011 and found it closed. Open until 4:30, said a sign, and it was closer to 5pm. Flat fluorescent lights held back the shadows and impending hush of the end of the teaching day. Aimlessly, I read the announcements taped up in the hallway, and learned that Ishmael and Marcel were no longer teaching together. The hallway outside the offices was the department’s closest thing to a town square. In a period where French universities had only partly embraced digital technology, it was a testament to the persistence of print and bulletin-board culture. The walls brimmed with handwritten or taped-up notices to the students, instructions about student projects and canceled classes, announcements of conferences, political manifestos and forgotten posters. In a few yards of concrete-block corridor, alienation and sociability and bureaucratic flatness commingled. At times the students lined up in the hallway to see the secretary, and it would overflow with bodies between classes in the department’s main teaching space, A028, just next door.

As I left the hallway, I ran into one of the professors, who seemed happy to see me. “The situation on campus is getting harder and harder,” he explained. Not everyone was on board with Paris 8’s plans for coping with the neoliberal “university autonomy” reforms (Rose 2019), and the president of Paris 8 was said to have a paranoid streak, apparently refusing to speak to people who disagreed with him. Moments later, a more senior professor showed up. We shook hands decorously, and I listened to some complaints about the president’s unilateralism and about bending university regulations. I didn’t get all the jokes, but I laughed anyway. Ishmael soon appeared on the scene too, and our emergent group, all male, went off together to inspect the new office of a philosopher who had recently been elected Director of the Arts and Philosophy Division. The new Director nonchalantly took out his pipe and smoked beneath a No Smoking sign mounted permanently to his wall.

A hundred yards down the hallway was the place where the students hung out: a cafeteria that served tiny coffees and sandwiches. My sociologist friend Charles Soulié described it to me as the main hangout for foreign students. After you had been around for a year, the sense of anonymity started to dissipate. I came in one day to a strange meeting of eyes. Even before entering, I saw by the windows at one of the tall standup tables my friends Michel and Anne-Marie. They were older students in their sixties, who had decided to get philosophy degrees in their retirement, aided by then extremely low tuition costs. I always found it somewhat utopian to have almost free public higher education.

As I arrived, they finished their coffees and came towards the exit, and we greeted each other.

“I didn’t want to interrupt you!” I said.

“We’d finished, we’d covered it all, we agreed on almost everything, which isn’t a bad thing…”

“What are you talking about?”

“Everything and nothing, as usual [tout et rien, comme d’habitude].”

That was what our ordinary life was like: talking about “everything and nothing, as usual.” A casual sociability in an otherwise alienating space. For a moment it almost felt like home.