Other marginalized students developed a more agentive relationship to campus space. Etienne, the young man from UFR0, took a minor shine to me. I never knew what he studied, but he was plainly a working-class banlieue figure, racially ambiguous to me. I never interviewed him formally. He was one of the many subaltern subjects at Paris 8 whose visceral distrust of institutions made me disinclined to introduce my tape recorder. But Etienne did appreciate a different recording device, my camera, since he had none of his own and he was an enthusiastic graffiti artist.

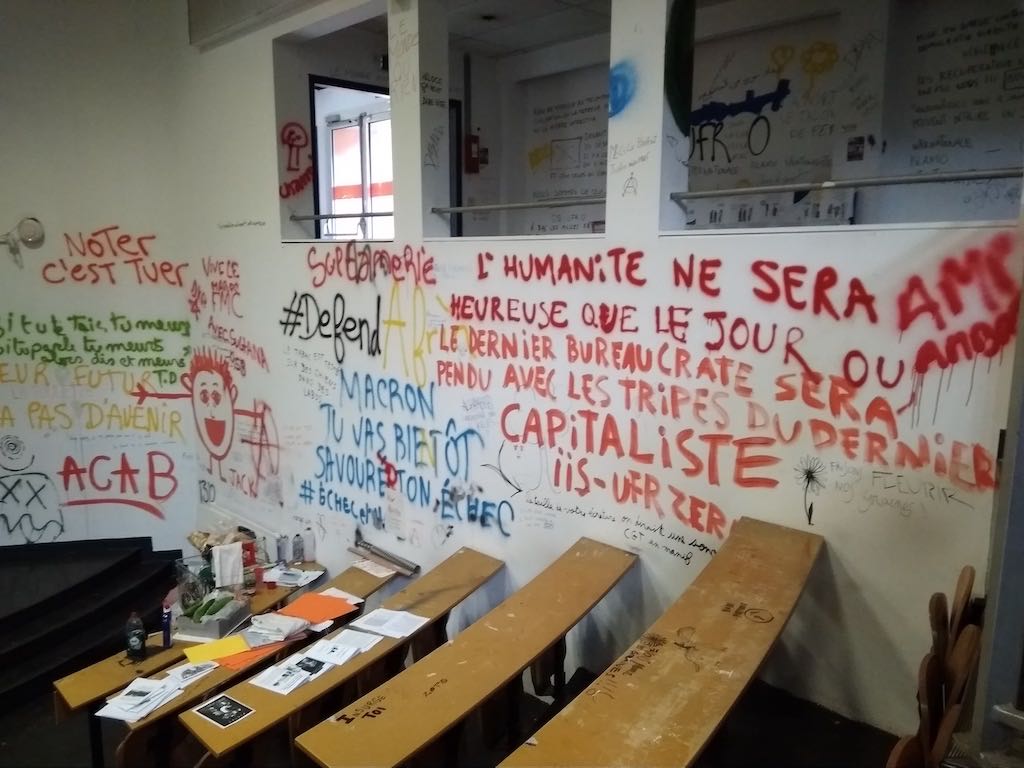

The graffiti at Paris 8 was a constant presence. It was certainly not everywhere, but it was common enough that its appearance in public spaces was rarely surprising. It tended to explode during moments of student protest and occupation, when the protesters temporarily had free reign in campus spaces. It was concentrated on the campus’s older buildings, especially in the most remote corridors, stairways and courtyards. The university did not have the resources to remove it all.

Much of the graffiti was political. It was closely associated with another major form of unofficial visual expression on campus: the omnipresent posters, activist flyers, stickers and banners that lined the campus spaces, particularly the main entrance to campus. But unlike the posters, the graffiti acquired a particular power to signify degradation and, via the chain of cultural stigmas that we examined earlier, to signify the banlieue itself. Graffiti was associated with other signs of banlieue abjection and criminality, such as theft, vandalism, and generalized uncleanliness.

There is no necessary connection between graffiti and the banlieue. All sorts of French university buildings contain graffiti, even at the Sorbonne in central Paris. May 1968 was famous for its radical graffiti, which may have been construed as a sign of disorder but was not associated with the banlieue. Nevertheless, graffiti has become a banlieue signifier in the contemporary Paris region. To arrive in Paris by train involves traversing the banlieue, witnessing scattered encampments of the homeless and masses of graffiti alongside the railroad. One can find graffiti scattered across Saint-Denis too, not so much in the downtown or on populous streets, but in liminal zones, under bridges or in empty spots. Ironically, Paris 8’s campus was possibly the most heavily tagged space I ever saw in Saint-Denis.

Etienne was himself an ambiguous, liminal figure, the only graffiti artist I ever met in person. His graffiti practices were also eloquent commentaries on the dilemmas of dwelling in a banlieue university. In fact graffiti itself was a form of dwelling in the university, and a way of contesting the local relations of reproduction. In Spring 2010, there was a protracted student occupation of a restaurant, whose spatial politics we will examine below. During my visit to the occupied space, I ran into Etienne, who had taken full advantage of the unobstructed access to campus spaces that the occupation afforded him. He wanted to give me a tour of his extensive graffiti work, and was eager for me to photograph the results, asking me to send him the results.

The ensuing graffiti, generally taking the form of quips and slogans, spoke volumes about Etienne’s radical form of subaltern, masculine consciousness. It made clear, above all, who his enemy was: the police. One tag read “Anti-cop: in or out of uniform.” Another made clear the lethal scope of this vision: “A good cop is a dead cop.” A third made clear the subversive relationship that opposed the campus occupiers to the security guards: “They are sentries, let’s be pirates.” And a series of other slogans, like “Anti-France” and “Property is Abolished,” made clear a generalized opposition to the state apparatus.

Etienne was particularly proud of a large-format tag in English, “Loveless (we need love).”

The “loveless” slogan was further surrounded by a whole series of masculinist love slogans. “It’s not love but the lack of love that we replace with sex,” attributed to an illegible name. Just left of “Loveless,” Etienne continued the ruminations on heterosexual voyeurism that I had heard at UFR0: “You please me but you don’t see me.” Nearby he had painted further English slogans: “We need love, fuck money,” and “Give me love forever.” Farther off, other tags, perhaps not by Etienne, made more violent sexual statements.

The graffiti constituted a medium of especially unrestrained speech, since it was anonymous and public. The content of these tags seemed to be some kind of commentary on marginalized masculinity at Paris 8. Etienne’s graffiti presented him as someone suspended between heterosexual desire and state interpellation, caught between loathing for the state apparatus and craving for love and aggressive heterosex. One can read these messages as symptoms of a toxic abjection, given the violent desire to kill the police and the intensely objectifying relation to women. Indeed, women’s voices had no place in this masculinist discourse, and Etienne seemed to project onto their bodies an imaginary solution to his own sense of sexual lack.

Without downplaying the disturbing content of Etienne’s slogans, we can also sense a desire to overcome his marginal social location. Through their very assertiveness, they illustrated his agency, made him visible, and manifested his desire to desire. To get “love” would perhaps have put an end to the loneliness that Etienne seemed to feel in his everyday social life, which was primarily with other young men. And to kill the police would have been, symbolically, to reverse the actual power relations of banlieue policing: the fantasy was a symbolic annihilation of the apparatus that seemed bent on annihilating people like himself.

The banlieue was more generally marked by strategies of subaltern reappropriation. Many of these involved the transcendence of legitimate forms of motion, via jumping turnstyles, parkour, or just hanging out in the street, and thereby existing publicly, taking up space. In this sense, it is telling that UFR0 met not in a classroom — which could likely have been arranged — but at a table in a campus hallway. A second form of spatial appropriation was the graffiti, which was a means of redecorating and resignifying the campus space. Etienne’s graffiti was no doubt meant to take power back from the campus authorities, to make security forces feel a little threatened, and to make manifest his desire for women. Yet I suspect that Etienne’s graffiti was above all meant to speak to men like him, with whom he sought to share his sense of precarity, of social antagonisms, of political righteousness and legitimate rage in the face of all these. It made the space theirs. And by asking me to document the results, he sought to get outside recognition of his spatial tactics.

These strong, non-normative assertions of subaltern presence on campus, such as Etienne’s graffiti, did not go unchallenged. The affront to the campus authorities and their normative “university community” was real, and it was met with strong efforts to overcome and erase it. Many considered the graffiti to be a pure degradation.