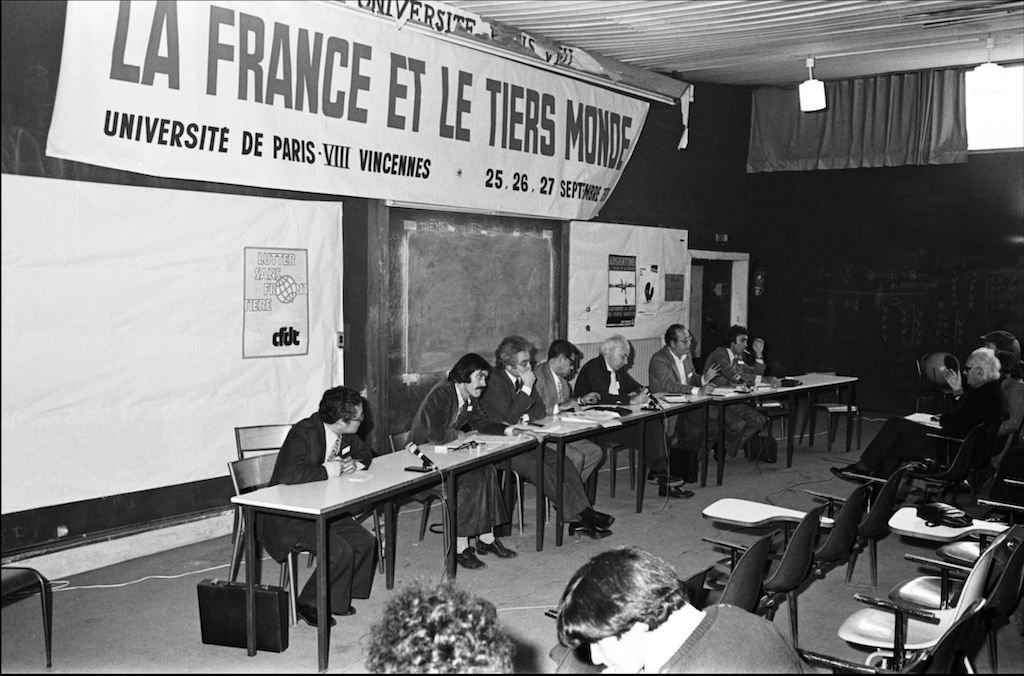

French radical philosophers of the 1960s embraced international revolution, and in turn they were largely shunned by mainstream French academia.[1] Yet the Paris 8 Philosophy Department still needed to survive institutionally. How could such a department survive in the conservative French academy? In a word: through international expansion. The global academic market offered a diversified student pool, international collaborators, institutional allies, and international legitimacy. By the time of my fieldwork, this internationalist orientation was long settled; the Department was the most internationally-focused philosophy program in France.

The mainstream academic system viewed this in creepy technocratic terms: “The LLCP [philosophy research laboratory][2] is successfully conducting a logic of ‘exportation’, especially in South America and Africa, by way of numerous partnerships, by co-organizing research projects, by participating in numerous conferences, and by hosting numerous foreign doctoral students” (AERES 2013:8). In short, it was a philosophy department in Paris that became enmeshed in trading partnerships with the global South and with the postcolonies. How should we understand an intellectual exchange between a former colonial empire and the postcolonial world?

I would note that that contemporary capitalism, always a crisis-prone system, has continued functioning in part thanks to what Marxist geographers term the “spatial fix.” When capitalist production reaches the limits of its contradictions and comes to an impasse in some particular site, capital can simply relocate itself to some more favorable site elsewhere in the world, finding a “spatial fix” for its impasse (Harvey 1981). After 1968, everything happened as if the Philosophy Department were following just such a logic. Facing a precarious situation within the national field of philosophy in France, it developed a spatial fix for its problem.

The Philosophy Department, in particular, was driven by a permanent imperative to accumulate symbolic capital and to ceaselessly produce.[3] The university system demanded that it produce new graduates, new research publications, and new “scientific activity.” Indefinite growth was not necessarily expected. But the Department was at least supposed to maintain its accustomed outputs. In an increasingly quantified assessment system, student metrics were especially scrutinized. The 2013 national evaluation noted skeptically that doctoral enrollments have “slightly fallen: 202 currently enrolled, against 229 in 2008” (AERES 2013:10).

If the Philosophy Department was organized around a “spatial fix,” having partly abandoned the national market in favor of the postcolonial and global market (especially at the doctoral level), then this fix was not without further contradictions of its own.

1) The ideological place of foreigners was at odds with the social experience of studying at Paris 8. Ideologically, foreigners of all continents were welcomed at Paris 8. But in practice, life for foreign students in the Paris region was often marginalized, segregated and economically precarious.

2) Intellectual reproduction became radically decoupled from professional reproduction. If you were enterprising, self-motivated, and able to find a good dissertation director, you might have a good intellectual experience at Paris 8. But there were no jobs waiting for you afterwards. It was very difficult to get an academic position in France, and the jobs continued to go mainly to white French academic elites. The neocolonial bargain offered to foreign subjects at Paris 8 was, in essence, to get a degree and then go home. And indeed, many postcolonial subjects did return to university positions in their home countries.

3) The Philosophy Department endorsed emancipatory project of transcending nationalism and Eurocentrism in global philosophy. But the spatial fix that sustained the Department itself presupposed ongoing structural inequalities in global higher education. To draw in hundreds of students from around the world, Paris 8 needed to offer something that was not readily obtained closer to home. The draw may have been the symbolic force of getting a French credential, or the training available in the Department, or the access to Parisian philosophical networks and academic venues, or merely the chance to continue practicing as an intellectual in exile. The attraction varied with individual circumstance. But what is clear is that Paris 8 also needed its metropolitan advantage over the peripheries — the very advantage that it then sought to transcend intellectually.

My aim in this chapter is not merely to show that a spatial fix and a neocolonial bargain existed. The actors established this themselves, all but openly. My aim here is instead to ask: how was this bargain lived? Let us first look at how internationalism was framed institutionally, and then turn to five specific cases: those of a Haitian and an Egyptian doctoral student, of a white French professor who had established strong Latin American ties, and of two North African administrative workers.

-

Most of the “French Theory” stars did not become professors at the Sorbonne, which was the pinnacle of French academic reproduction (Bourdieu 1988, Lecourt 2001), and their disciples and followers were even more totally excluded from the academic system. Senior professors at Paris 8 felt this exclusion viscerally. “You kind of have to mourn your academic career,” Georges Navet told me as he explained his unconventional research topics. Students from Paris 8 had a hard time with job placement, and the Department’s degrees were nationally unaccredited from the 1970s until the late 1980s. While the Philosophy Department endured as a department, it remained marginalized and largely shut out of the national field of philosophy in France. As the national assessment agency put it in 2013, describing the department’s doctoral program and research laboratory, “It is no doubt a bit atypical in the French university landscape, for, if it is very widely known in the intellectual milieu, it ‘interacts’ relatively little with the academic milieu: no projects funded by the National Research Agency, few contacts with other centers of contemporary philosophy (ENS Ulm, Toulouse, etc)” (AERES 2013:8). ↩

-

The research laboratory was technically a distinct organizational entity, operated separately from the Philosophy Department (although affiliated with it). The Philosophy Department, which belonged to the university’s Arts Division (UFR0), held the faculty appointments and managed the undergraduate and Master’s programs. The research laboratory, which belonged to a Doctoral School, was entitled the Laboratory for Research and Study on the Contemporary Logics of Philosophy (LLCP), was comprised of all the doctoral students, most of the departmental faculty and a few outside members. The French title is Laboratoire d’études et de recherches sur les Logiques Contemporaines de la Philosophie. A French research laboratory in the human sciences is essentially what an Anglophone might call a research center: an organizational entity with its own budget, its own events and programs, and possibly facilities or specific infrastructure. ↩

-

To be sure, the Philosophy Department was not a capitalist enterprise and it was not highly motivated by economic profit or even by the accumulation of material resources. The national evaluation agency frequently commented that its material resources (money and facilities) were grossly insufficient for a department of its size, and noted that it did not appear to be seeking significant outside funding. Yet as Pierre Bourdieu amply demonstrated in his research on French academia, economic capital is not the only kind of capital. Unlike Bourdieu, I do not read social life mainly in terms of capital accumulation and social domination. But without reducing everything to them, these processes do exist and they matter. ↩